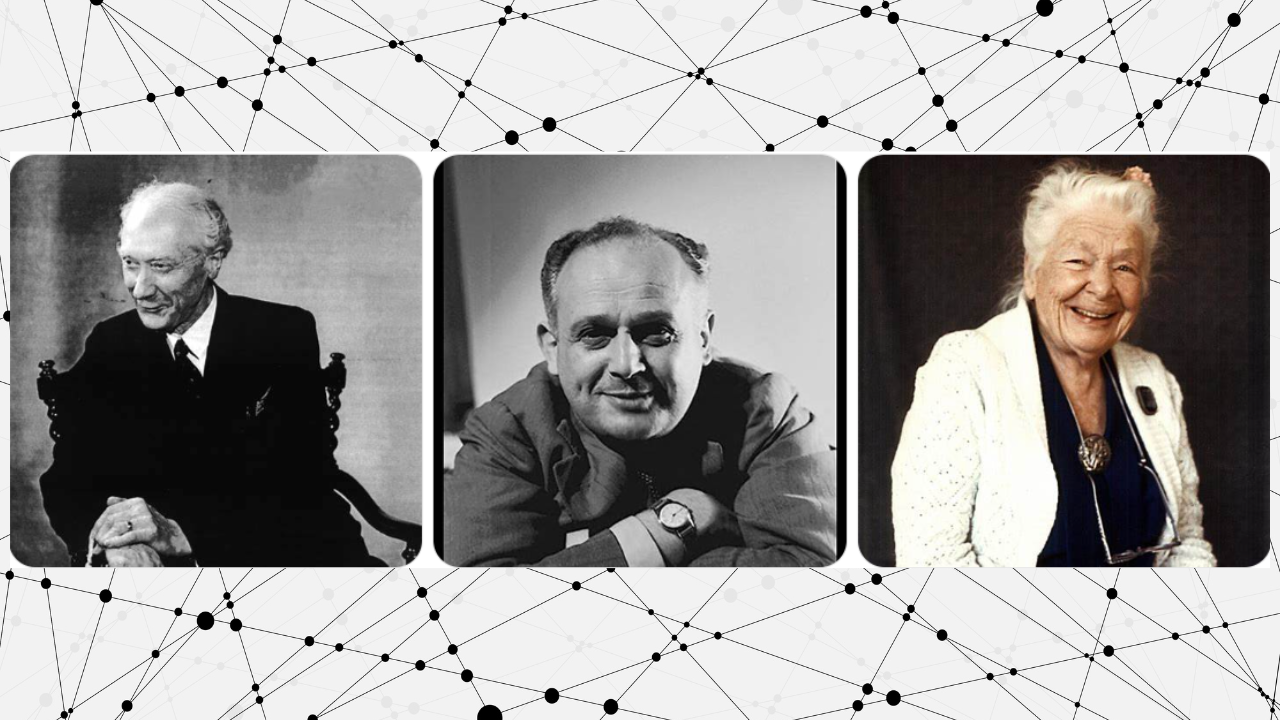

Somatic Pioneers: Feldenkrais, Rolf, and Alexander – Connections and Comparisons

Introduction

Moshe Feldenkrais, Ida P. Rolf, and F. Matthias Alexander were pioneers of somatic education in the 20th century. Each developed a unique method for improving human posture, movement, and wellbeing – the Feldenkrais Method®, Rolfing® Structural Integration, and the Alexander Technique, respectively. All three approaches seek to enhance bodily awareness and function, yet they emerged from different backgrounds and emphasize distinct philosophies and techniques. This report delves into the historical relationships between Feldenkrais, Rolf, and Alexander (including any documented meetings or correspondence) and provides a comparative analysis of their methodologies. Key similarities and differences in guiding principles, techniques, and intended outcomes are examined. To ground the comparison in practice, examples of lessons or exercises from each method are provided. We also explore how these approaches can complement one another in an integrated somatic learning program. A summary table is included for a concise overview of their differences and similarities. (Citations are provided in brackets, and full sources are listed in the final section for clarity.)

Historical Connections Among the Three Innovators

Despite developing their methods independently, Feldenkrais, Rolf, and Alexander were aware of each other’s work – and in some cases, personally interacted:

- Ida Rolf and F. M. Alexander: Ida Rolf (1896–1979) never met Alexander in person (Alexander died in 1955, before Rolf’s work gained prominence). However, Rolf was familiar with the Alexander Technique and counted it among the modalities she explored during the development of her own method. In the 1940s, after returning to the U.S. from Europe, Rolf studied various alternative therapies and mind-body practices – including osteopathy, yoga, homeopathy, and the Alexander Technique

archives.barnard.edu

. This exposure influenced her thinking on posture and body organization. Rolf’s papers and biographies do not indicate direct correspondence with Alexander or his immediate circle, but the Alexander Technique’s principles (such as improving posture through awareness rather than brute force) resonated with her. Indeed, Rolf’s early concept of Structural Integration benefitted from the groundwork laid by earlier pioneers like Alexander. We might say Alexander was an indirect mentor to Rolf, in that she built upon some of the same foundations of posture and consciousness in the body.

- Ida Rolf and Moshe Feldenkrais: By the 1970s, Rolf and Feldenkrais were contemporaries working in the emerging human potential movement, and they became colleagues and personal friends

feldenkraismethod.com

. Both taught at growth centers such as the Esalen Institute in California, where cross-pollination between modalities was common. They met on multiple occasions – notably in the early 1970s at Esalen. Accounts describe Rolf and Feldenkrais dining together and discussing their work

feldnet.com

. Rolf, who was typically reticent to name influences on her work, openly acknowledged that Dr. Feldenkrais had influenced her: when asked by psychologist William Schutz who had shaped her approach, Rolf replied, “Dr. Feldenkrais — his book Body and Mature Behavior — the chapter on gravity.”

feldenkraismethod.com

. This is a striking admission, as Rolf’s method centers on aligning the body in gravity, a theme Feldenkrais also examined. Their friendship is further evidenced by personal letters. For example, in 1976 Feldenkrais wrote Rolf a warm birthday letter, and upon her passing in 1979 he eulogized her as “a very good friend of mine and a formidable woman”

feldenkraismethod.com

. During their friendship, Feldenkrais and Rolf exchanged ideas and even good-natured debates about their respective approaches. They recognized that they were essentially working toward similar goals (better human integration and function) from two angles – “Structural Integration” (Rolf’s term) versus “Functional Integration” (Feldenkrais’s term for his hands-on work)

rolfing.org

. A letter from Feldenkrais to Rolf in 1976 encapsulated their shared perspective: “Structural Integration and Functional Integration have more in common than the word that connects them. Indeed, in the case of humans, structure and function are meaningless one without the other; so that when you integrate structure, as nobody else can, you improve functioning.”

rolfing.org

. This mutual respect did not mean they always agreed on details – in the lively atmosphere of Esalen, observers noted spirited arguments among somatic pioneers. In one humorous anecdote, Rolf, Feldenkrais, and references to Alexander’s ideas all surfaced in a debate about the proper position of the third cervical vertebra – each had a different opinion on ideal alignment

esalen.org

. Such stories highlight both their differences in perspective and the collegial environment in which these innovators learned from one another.

F. M. Alexander and M. Feldenkrais: Frederick Matthias Alexander (1869–1955) created the Alexander Technique decades before Moshe Feldenkrais (1904–1984) developed his method. In the 1940s, while in Britain, Feldenkrais sought out Alexander’s teaching. Feldenkrais took lessons with F. M. Alexander, learning directly from the elder teacher

en.wikipedia.org

. This student-teacher relationship was brief; sources indicate that Feldenkrais studied with Alexander and even expanded upon Alexander’s ideas in his own writings, situating them in a scientific and neurological context

catherinemccrum.com

. A later account suggests the two men eventually quarreled – likely due to differing viewpoints or personalities – but Alexander’s influence on Feldenkrais remained significant

catherinemccrum.com

. For example, Feldenkrais’s 1949 book Body and Mature Behavior echoes some Alexander Technique themes (such as the role of gravity and posture in human functioning) but with added evolutionary and neurodevelopmental theory. There is no evidence of extensive correspondence between them beyond Feldenkrais’s period of study; however, Feldenkrais’s exposure to Alexander’s method helped inform his own approach.

In summary, historically Alexander directly taught Feldenkrais, and Alexander’s ideas influenced both Feldenkrais and Rolf. Rolf and Feldenkrais in turn became close colleagues, openly acknowledging each other’s contributions to somatic work. All three were connected through the evolution of somatic education, forming a lineage: Alexander’s foundational work on postural habits laid groundwork that Feldenkrais and Rolf expanded in new directions. By the late 20th century, their methods were often discussed together and even combined by practitioners who trained in multiple disciplines.

Comparing Their Methodologies and Philosophies

Though Feldenkrais, Rolf, and Alexander shared the broad goal of improving human functioning through greater body awareness, each developed a distinct methodology. Below we compare their guiding principles, techniques, and intended outcomes, noting where they converge or diverge:

Philosophical Foundations and Guiding Principles

-

Moshe Feldenkrais – Functional Learning and Awareness:

The Feldenkrais Method is fundamentally an educational approach grounded in the idea that awareness leads to improvement. Feldenkrais believed that through gentle exploration of movement, the nervous system can learn and reorganize for better posture, balance, and coordination. A famous Feldenkrais maxim is: “Make the impossible possible, the possible easy, and the easy elegant.” This captures his emphasis on gradual learning: students start with movements that are extremely simple or small, often ones they initially find difficult, and through slow mindful practice, they expand their ability until those actions become effortless. Guiding Principles in Feldenkrais include: awareness of differences (paying attention to subtle changes), reduction of effort (using minimal force to avoid habitual strain), and variation (trying novel movement patterns to break out of rigid habits). Feldenkrais viewed the body and mind as inseparable in forming “patterns of movement” or habits; changing how one moves can alter how one thinks and feels, and vice versa. He was influenced by developments in physics, neurology, and psychology, and saw his work as “self-education” rather than therapy. Importantly, Feldenkrais also stressed the role of the environment and gravity – like Rolf and Alexander, he understood that how we organize ourselves in gravity is key to our health

rolfing.org

. However, instead of manually imposing alignment, Feldenkrais’s philosophy is to improve function (movement) and let structural alignment emerge from that improved function.

-

Ida Rolf – Alignment in Gravity and Holistic Integration:

Rolf’s work, Structural Integration (later known as Rolfing), is underpinned by the principle that “form governs function” – in other words, if the body’s structure is aligned properly, efficient function will naturally follow. Her guiding vision was of the human body as an arrangement of segments (head, torso, pelvis, legs, etc.) that could be realigned to a vertical axis (a central “Line”) for optimal balance in the field of gravity. Guiding Principles of Rolfing include: integration (considering the body as a whole interconnected system), balance in gravity (achieving an upright, effortless posture), and holism (recognizing that changes in one part affect the whole). Rolf, with her Ph.D. in biochemistry, also approached the body’s tissues scientifically – she focused on the myofascial system (the connective tissues that surround muscles and organs) as the medium of change. She observed that injuries, stress, and habitual poor posture create restrictive patterns in fascia, pulling the body out of alignment. By loosening and reordering these connective tissues, the body could “organize” itself into better alignment. An oft-cited Rolf saying is “gravity is the therapist.” What she meant is that once a body is optimally aligned, gravity – which formerly was a burden, dragging one down – becomes a supportive force that helps hold everything in place with less effort. Rolf’s approach was also holistic in a personal growth sense: she believed that improving a person’s physical structure could affect their emotional and psychological well-being. In her own words, Rolf saw her work not just as fixing aches and pains but “changing the human being” and evolving their potential. This transformational aspect aligns with Feldenkrais’s and Alexander’s view of their methods as tools for overall self-improvement, not just physical therapy.

F. M. Alexander – Conscious Inhibition and “Use of the Self”:

The Alexander Technique is rooted in the insight that the way we habitually use our bodies affects our overall functioning. Alexander’s core discovery was the importance of the head-neck-spine relationship, which he termed the “primary control,” in governing posture and movement. He observed that unconscious habits (for example, tensing the neck or slumping the spine) were at the root of his voice problems and many others’ ailments. Guiding Principles of Alexander’s approach include: awareness in activity, inhibition, and direction. Inhibition, in Alexander terms, means pausing to prevent an automatic, habitual response – essentially unlearning bad habits by refusing to do them, creating a moment of conscious choice. Direction refers to the gentle mental guidance one gives oneself (e.g. thinking of the neck free, the head releasing upward, the back lengthening) instead of actively “doing” a movement in the old way. Summed up, Alexander taught the importance of “conscious control” over one’s manner of use: by becoming aware of how we initiate and carry out any action, we can choose a more efficient, easeful way. Alexander’s philosophy was influenced by the evolutionary idea that humans, as conscious beings, could guide their own growth. He did not frame his work as exercise or treatment, but as a reeducation of the psycho-physical self. Like Feldenkrais and Rolf, Alexander acknowledged gravity’s role – he often worked with students standing or sitting to teach them not to collapse downward – but his method aims to improve how a person balances and moves in gravity by changing internal habits rather than manipulating their body from the outside. His famous quote “Use affects Functioning” encapsulates that how you use your body (habitually) will affect everything you do (function); improve the use, and overall functioning improves.

Common Ground:

All three pioneers shared a holistic, somatic philosophy that the mind and body are deeply interconnected. They each recognized that habitual patterns (whether muscular, postural, or movement-based) can limit a person’s potential, and that conscious intervention can lead to new patterns and improved well-being. None of them was interested in quick fixes or narrow symptom-based treatment; instead, they sought to educate the individual to better care for and organize themselves. Each method in its own way addresses the impact of gravity and posture: Alexander talked about the head-spine alignment, Feldenkrais wrote about the pressure of gravity and our skeletal support, and Rolf outright made gravity central to her work. They also all believed in not forcing the body. For example, Rolf famously said “If at first you don’t succeed, get the hell out!” – meaning if direct force isn’t working, don’t push harder, but rather approach indirectly

. This is quite similar to Feldenkrais’s insistence on gentle, non-forceful movements, and Alexander’s emphasis on not forcing oneself into “correct” posture. Thus, a key similarity in philosophy is the respect for the body’s wisdom and the use of gentle, mindful change rather than brute force to improve posture and movement.

-

Feldenkrais Method Techniques:

Feldenkrais designed two formats in his method: Awareness Through Movement (ATM) lessons and Functional Integration (FI) lessons. ATM classes are group sessions (or done solo with audio/book guidance) in which a teacher verbally leads students through gentle movement sequences. These movements are often done lying on the floor, but sometimes in sitting or other positions, to minimize strain and enhance awareness. An ATM sequence might involve, for example, slowly rolling the head, sensing how the movement travels down the spine, or exploring the motion of the pelvis in various directions (the classic “pelvic clock” lesson). Students are encouraged to move with no more effort than absolutely necessary, to focus on sensations, and to notice differences (left vs right, before vs after, etc.). Rather than stretching or strengthening muscles, ATM lessons refine the coordination of the whole body. Each lesson is like a movement riddle or exploration that leads the student to discover an easier way of functioning. Functional Integration, on the other hand, is a one-on-one hands-on technique. An FI lesson typically has the student lying fully clothed on a low table while the practitioner gently moves different parts of their body. This is not a massage – the practitioner uses supportive touch and slow manipulations to help the student feel new movement possibilities and connections in their body. For instance, the practitioner might delicately rock a person’s foot to see how the movement transmits up through their hips and spine, subtly improving that transmission. Throughout, the Feldenkrais practitioner is “listening” through their hands – they feel how the person’s body responds and where there is resistance or ease – and they guide without forcing, within the comfortable range of motion of the student. The technique is very gentle; Feldenkrais joked that if anyone watching can tell what the practitioner is doing, they are doing too much. Both ATM and FI aim to create conditions for the student’s nervous system to learn. After lessons, people often report not only reduced pain or stiffness but also a feeling of lightness and easier posture – achieved without any direct instruction to “stand up straight,” but as a byproduct of better movement organization. Feldenkrais techniques also often incorporate imagination and attention: students might be asked to imagine a movement before doing it, or alternate tiny movements with periods of rest to let the brain absorb changes. The overall practice is very exploratory and adaptive to each person, rather than a fixed routine. -

Rolfing (Structural Integration) Techniques:

Rolfing is primarily known for its hands-on, deep tissue manipulation. Dr. Rolf developed a standard series of ten sessions (the “Basic 10”) that systematically address the entire body’s fascia, each session with specific goals (e.g., Session 1 focuses on freeing breathing by working the chest and arms; Session 2 might focus on feet and lower legs to establish support, and so on). In a Rolfing session, the client usually lies on a massage table (and sometimes sits or stands for certain tests or movements). The Rolfer uses their hands, knuckles, even elbows at times to apply firm pressure and stretch the fascia in targeted areas. The technique can at times be intense; Rolfers aim to work at a depth that the tissue responds to, which may cause some discomfort, though modern Rolfing tends to be gentler than the reputation of Rolf’s early years (the old joke “It worked, but it hurt” is less apt today). An example technique is the Rolfing soft-tissue release: a Rolfer might slowly drag fingers or elbows along a tight band of muscle and fascia (say, along the IT-band on the outer thigh or the muscles between the ribs) to elongate those fibers and break up adhesions. As they do this, they often instruct the client to breathe, move a limb, or make small motions to aid in the release. In fact, Rolfing is not purely passive – Rolfers frequently engage the client in active movement or perception. For instance, while working on the shoulders, a Rolfer may ask the client to gently rotate an arm or to notice how their shoulder blade glides, integrating the manual work with the person’s awareness. Additionally, Rolf Movement is a branch of the work that explicitly teaches clients movement and awareness exercises (often used between or after the hands-on sessions). These might include things like “arcing” (slowly shifting weight while sensing the spinal alignment) or pelvic tilts to encourage a coordinated use of core muscles

hudsonvalleyone.com

. Dr. Rolf also had some favorite movement cues, such as her famous “arm rotations” exercise to balance the shoulder girdle – clients are taught to rotate their arms in specific ways to connect shoulder and core stability. Throughout the Rolfing process, the Rolfer periodically has the client stand, walk, or perform a simple movement to assess changes in alignment and coordination. Photographs are sometimes taken before and after the 10-series to document changes in posture. The technique’s overall aim is to reposition and integrate the body: after releasing restrictions, the practitioner guides the body segments into improved alignment (for example, encouraging the pelvis to sit level, the spine to stack, the head to balance easily on top). Rolfers use considerably more physical pressure and direct structural change than Feldenkrais or Alexander practitioners – Rolfing literally changes the shape and glide of tissues. But a skilled Rolfer does this in dialogue with the client’s nervous system, often saying that it’s not the Rolfer “fixing” the person but creating the right conditions for the person’s own body to change itself. After a Rolfing series, clients often report feeling taller, straighter, more open in areas that were tight, and better balanced. Many also describe psychological or emotional releases occurring during sessions, reflecting Rolf’s view that bodily and emotional patterns are intertwined (“the issues in the tissues,” as it’s sometimes said).

-

Alexander Technique Practices:

The Alexander Technique is traditionally taught in one-on-one lessons (though group classes and self-practice are also possible). A typical Alexander lesson involves the student performing simple everyday actions – such as standing, sitting in a chair, walking, bending, or speaking – while the teacher observes and gives guidance. The hallmark of Alexander work is the use of the teacher’s gentle hands-on contact combined with verbal coaching to help the student become aware of unnecessary tension. For example, an Alexander teacher might have a student sit and stand from a chair repeatedly. As the student begins to stand, the teacher might place a hand at the back of the student’s neck or head (and perhaps another on their back or chest) to detect and prevent the habitual tensing or collapsing that usually occurs. The teacher will encourage the student to stop and inhibit the immediate impulse (which might be to jerk the head back and down, stiffen the legs, etc.), and instead to think of allowing the neck to be free, the head to release forward and up, and the knees to move forward. With practice, the student learns to perform the action with much less strain and a feeling of openness. Another classic element of Alexander lessons is “table work”: the student lies in a supine, semi-supine position (often with knees bent and head resting on books) while the teacher uses their hands to gently lengthen and release tension in the student’s limbs, neck, and back. This table work is somewhat analogous to Feldenkrais FI in that the student is passive and the practitioner is guiding, but Alexander touch is usually even lighter – it’s often described as a very delicate coaxing of the muscle tone rather than any sort of deep manipulation. There are no exercises to practice in Alexander Technique in the conventional sense. Instead, the “practice” is applying the Alexander process to all activities of life. Students are often assigned something like “constructive rest” (lying down as described for 10–15 minutes to consciously release tension) or asked to bring awareness and inhibition into a specific daily task (like brushing teeth or playing an instrument). In Alexander lessons, the emphasis is on real-time awareness and correction: you learn to catch yourself in the moment of tightening or misaligning, and to make a new choice. Over time, this retrains your nervous system and muscles to adopt a more easeful organization by default. Notably, Alexander work does not involve any forceful adjustment or deep tissue work – it’s very much about the student’s active mental participation and subtle guidance from the teacher. The Alexander Technique is often described as “the technique of not doing” – meaning you improve by learning what not to do (i.e., to stop interfering with your natural poise).

Key Differences in Technique:

The level of physical touch and manipulation is a primary differentiator. Rolfing is largely interventionist, manually altering tissue structure, whereas Feldenkrais and Alexander are more educational, with Feldenkrais using gentle touch/movement and Alexander using light touch plus the person’s own action. Feldenkrais occupies a middle ground between Alexander and Rolfing in terms of touch: Feldenkrais FI involves the practitioner moving the person’s body (but gently and always within easy range), and ATM is verbally guided movement with no touch at all. Alexander lessons involve touch, but the touch is to guide the student’s own movement and awareness, not to directly reshape tissues. Another difference is group vs individual format: Feldenkrais ATM is commonly done in groups, making it accessible to many at once, whereas classical Alexander is one-to-one (though group introductory classes exist, they often still pair off with a teacher’s guidance). Rolfing is one-to-one bodywork (group classes exist only for teaching self-care exercises, not for the core manipulation work). Use of exercises also differs: Feldenkrais lessons are themselves movement “exercises” (though non-calisthenic in nature), and Rolfing may give exercises for homework; Alexander doesn’t prescribe exercise routines but instills a practice of mindful inhibition applicable to all activities. In terms of the student’s/passive role: Rolfing clients are relatively passive recipients during hands-on work (apart from some guided breathing or movement), Feldenkrais students are active movers in ATM (passive in FI but still internally engaged), and Alexander students are actively engaged mentally and often physically in every moment of a lesson. All three methods involve a high degree of practitioner skill and decision-making in tailoring to the individual – but the Alexander teacher’s role is more to coach and prevent interference, the Feldenkrais practitioner’s role is to create a rich learning experience (via verbal instruction or nuanced touch), and the Rolfer’s role is to physically intervene to change the tissue and alignment, then help the client adapt to that change.

Intended Outcomes and Effects

- Outcomes of Feldenkrais Method: People who engage in Feldenkrais typically seek improvements in flexibility, coordination, pain relief, and overall ease of movement. The outcomes are often described as feeling lighter, moving more smoothly, and having a greater repertoire of comfortable movements. Because Feldenkrais addresses functional issues, it can help with anything from recovery after injuries to enhancing athletic or artistic performance. An important intended outcome is increased self-awareness – students become much more attuned to their bodies, noticing early signs of tension or poor alignment and spontaneously self-correcting through the strategies they’ve learned. In the long term, Feldenkrais hoped to create “independent learners” who could continue to refine themselves. Many Feldenkrais students report improved posture incidentally – for example, after a series of lessons they find they stand or sit more upright without thinking about it – which comes from improved muscular coordination rather than conscious effort. Because the method engages the whole nervous system, benefits can also include reduced stress and enhanced cognitive or creative abilities (students often note they feel mentally refreshed or clearer after lessons). The method does not promise a cure for medical conditions, but by improving the organization of the body, it often alleviates chronic pain conditions (like back or neck pain) and can complement rehabilitation therapies. Feldenkrais also has specialized applications for children with developmental issues and people with neurological conditions, using the same principles of gentle, adaptive movement to improve function.

- Outcomes of Rolfing (Structural Integration): The most visible outcome of Rolfing is often improved posture alignment. Clients frequently demonstrate a before-and-after change: shoulders more even, chest more open, back straighter, and a longer, more balanced stance. Along with this structural change comes relief from many chronic pains and aches that were due to misalignment or tension – e.g., knee pain lessens once legs and pelvis are better aligned, or chronic headaches resolve after release of neck and jaw fascia. Rolfing recipients often report a feeling of being more balanced and stable on their feet, as well as a sense of lightness or fluidity in movement once the “drag” of bound tissues is removed. Another intended outcome is increased range of motion – tight areas like a stiff shoulder or a bent-over upper back become looser and can move more freely after Rolfing work. Because Rolfing can involve intense emotional release (some say memories or emotions “stored” in the fascia can be unlocked), clients might also experience emotional catharsis or positive shifts in mood and self-awareness. Dr. Rolf believed that integrating the physical structure could lead to a better functioning human being in all aspects, even suggesting a sort of uplift in one’s energy or outlook. Many clients indeed describe feeling more energetic or “integrated” as a whole person. Long-term outcomes: With Rolfing’s ten-series, the goal is that the body stays improved for a long time, especially if the person maintains it with movement awareness or occasional tune-up sessions. Rolfers often encourage clients to follow up the structural work with movement education (some Rolfers are certified in Rolf Movement or may refer to modalities like Feldenkrais or Alexander) so that the client’s movement habits adapt to their newly aligned body. Without such integration, there’s a risk that old movement patterns could gradually pull the structure back out of alignment. But ideally, a Rolfed body has a new equilibrium in gravity that is self-sustaining – gravity “flows through” the structure in a way that the person doesn’t have to fight against it constantly. rolfing.org

- Outcomes of Alexander Technique: Alexander Technique students commonly seek help for chronic neck/back pain, posture problems, tension (e.g., stage fright tension), or performance enhancement (especially actors, musicians, and dancers use it to improve their skill and avoid injury). The primary outcome is often described as improved postural poise – standing and sitting with less effort, with the head balanced freely atop the spine. Students frequently experience relief of pain or discomfort that was caused by longstanding postural strain or inefficient movement (for example, lower back pain from chronic slouching or neck pain from craning the head forward). Improved breathing and voice are also notable outcomes, since reducing chest and throat tension allows fuller breath and clearer vocal production (remember, Alexander originally developed his technique for voice loss). A successful Alexander experience leaves the student with a sense of being more calm yet alert, as releasing physical tension often reduces mental anxiety. Over time, practitioners of Alexander Technique often notice changes in their appearance and demeanor: they may appear more relaxed, move more gracefully, and even seem to have grown taller as their compressed spine lengthens out. One of the valued outcomes is self-management of stress and effort – Alexander students learn they have a tool to prevent and alleviate undue tension in any situation (whether at a computer, on stage, or doing housework). Like Feldenkrais, Alexander’s approach can indirectly foster personal growth; many people report increased confidence and mindfulness as they apply the technique’s principles in daily life. It’s worth noting that Alexander Technique, as a learning process, typically requires a series of lessons (often 20–30 or more) for substantial change, and the “result” is something maintained by the individual’s continued practice of awareness, rather than a permanent fix administered by the teacher. Ultimately, the outcome is an individual with a better “use of the self,” meaning they carry themselves and respond to stimuli in a more optimal way habitually.

Summarizing Similarities/Differences in Outcomes:

All three methods aim to reduce unnecessary tension, alleviate pain, improve posture, and increase ease in movement. The differences are partly in emphasis: Rolfing explicitly targets the physical posture and fascial tension to yield structural changes, Feldenkrais targets movement coordination to yield functional changes (which often also have postural effects), and Alexander targets conscious habit change to yield improved use in any activity (also affecting posture). A point of convergence is that each approach ultimately benefits the whole person, not just the body. Many practitioners of these methods speak of increased vitality, improved self-confidence, and even changes in how they approach life challenges – all stemming from the embodied learning they have done.

Comparison Table: Feldenkrais Method vs. Alexander Technique vs. Rolfing

Techniques and Practices: How Each Method Works

Examples of Lessons and Exercises from Each Method

To illustrate how these methods work in practice, here are specific examples of lessons or exercises typical of each:

- Feldenkrais Example – “The Pelvic Clock” (Awareness Through Movement lesson): In this classic Feldenkrais lesson, the student lies on their back, knees bent, feet standing on the floor. They imagine a clock face on the back of their pelvis (with 12 o’clock toward the head and 6 o’clock toward the feet). Gently and slowly, they tilt the pelvis as if to point toward 12, then toward 6, exploring the tilt of the lower back. Then similarly they explore 3 and 9 (tilting pelvis to each side). Gradually, the student tries to “sweep” the pelvis around the circle of the clock, finding a smooth motion through all the “times.” Throughout, the instructor’s voice prompts awareness: Notice how your ribs respond when you tilt to 12… Let your jaw be soft… Are you breathing? By the end, not only is the pelvic region more relaxed and mobile, but the student often finds their lower back and hip tension has released, and their posture in standing feels easier (as the pelvis is now better aligned under the spine). This lesson shows Feldenkrais’s use of visualization (the imaginary clock), micro-movements, and attention to detail to improve coordination. Another brief example: “Rolling from Back to Side” – a lesson where students figure out how to roll comfortably by turning the head, letting the eyes lead, allowing the knee to fall, etc., learning how to distribute effort so the movement becomes effortless. Such lessons mimic developmental movements that infants do, thereby tapping into innate movement intelligence and improving core coordination.

- Alexander Technique Example – “Hands on the Back of the Chair” (Self-awareness practice): A common exercise Alexander devised for himself and taught to pupils is standing behind a chair, lightly resting hands on the chair back, and practicing bending the knees and hips (a bit like a squat or “monkey” position) with good use. The student is instructed to keep the back lengthening and the head releasing forward and up (not tucking down) as they bend. They stop and inhibit any tendency to either arch the back or collapse. With the teacher’s guidance, they learn to hinge at the hip joints while maintaining a neutral, elongated spine – a very practical movement used in picking things up from the floor or athletic stances. This seemingly simple act actually requires overcoming a lot of habit; many people either stiffen or slouch. By practicing this with awareness, the student gains a new pattern for bending. Another typical element of Alexander work is the “Whispered Ah.” Here, a student practices speaking or whispering a vowel sound (like “ah”) while maintaining a free neck and easy breath. It’s used to eliminate habit patterns of tightening the throat or gasping when vocalizing. The teacher might place a hand on the student’s back or chest to sense excess tension and remind them to release. Through whispered ah, the student learns to project the voice with minimal effort, a skill that directly benefits public speaking or singing. Additionally, constructive rest (lying in semi-supine with books under the head) is an Alexander exercise for daily practice: the student lies for 10 minutes focusing on releasing the neck, widening the back, and letting the floor support them. This helps undo the day’s tensions and sharpen awareness of posture habits.

- Rolfing Example – “Rolf’s Arm Rotations” (Movement integration homework): Dr. Rolf often gave clients a simple exercise to help integrate the shoulder girdle with the rest of the body. While standing or sitting, she’d have them raise one arm in front of them to about shoulder height, then rotate the arm outward (laterally) and inward (medially) in the shoulder socket, all the while keeping the arm straight. She emphasized that this rotation isn’t just about the arm – the person should feel the connected movements through their shoulder blade, and even into the spine and ribs. She might cue them to “feel the shoulder blade sliding down when you rotate out” or to connect the movement to the breath. This exercise, done gently and within comfortable range, helps organize the shoulder in relation to the back and chest. It can relieve shoulder and neck tension by teaching the body a more balanced alignment of the shoulder joint. In a Rolfing session, a Rolfer might do this with the client after working the shoulder muscles, to integrate the manual work into a functional pattern. Another example from a Rolfing session: Pelvic Lift for Lower Back Release. The Rolfer might ask the client (lying on their back) to slowly lift their pelvis a few inches off the table, then let it down, repeating a few times. While the client does this, the Rolfer uses hands under the sacrum or low back to feel how the movement occurs. The practitioner might identify a point of restriction (say, the low back is stiff) and then manually work on that area – perhaps applying pressure along the lumbar muscles – and then have the client try the pelvic lift again. Usually the movement becomes easier and higher after the work. This interplay of movement and manipulation is characteristic of Rolfing’s integrative approach. Lastly, a hallmark Rolfing example is simply the Session 1 focus on breath: The Rolfer might spend much of the first session loosening fascia in the chest, ribcage, diaphragm area, and neck to free the client’s breathing. The client may be asked to take breaths, to sense where breath is restricted, and after the work they often report breathing feels much deeper or fuller. This sets the stage for all further work, since breath is central to vitality and to how the spine organizes.

These examples demonstrate the practical differences: Feldenkrais lessons feel like gentle movement explorations often done solo or in a quiet group; Alexander practices often involve everyday motions made conscious with a teacher’s subtle help; Rolfing exercises tie into or follow intensive hands-on releases to ensure the body learns a new alignment. Despite differences, notice that all involve awareness and paying attention to the body, not mindless repetition. Whether it’s visualizing a clock under your back, noticing the neck as you stand up, or feeling your shoulder blade in an arm movement, the common thread is increased somatic awareness.

How the Methods Complement Each Other

Rather than seeing these approaches as mutually exclusive, many experts consider them complementary facets of somatic learning. Each method has strengths that can support or enhance the others:

- Combining Structure and Function: As Moshe Feldenkrais himself noted to Ida Rolf, “structure and function are meaningless one without the other”

rolfing.org

. Rolfing’s strength is in structural change – it can quickly free areas of physical restriction, giving a person a new alignment. Feldenkrais and Alexander excel in functional change – they train the person in using themselves more efficiently. Used together, a client might receive Rolfing sessions to liberate the body’s alignment, then use Feldenkrais or Alexander lessons to learn how to move in that improved alignment so that old habits don’t pull them back. In practical terms, Rolfing could improve the range of motion in someone’s shoulders and spine; Feldenkrais lessons could then teach that person how to integrate the new range into bending, reaching, or athletic movements. Conversely, doing Feldenkrais or Alexander first can prepare a person to get more out of Rolfing – the person will be more aware during the Rolfing sessions and might respond faster since their nervous system is already primed for change. In fact, Rolfing today incorporates movement education and awareness (Rolf Movement) very much akin to Feldenkrais principles

rolfing.org

. Ida Rolf Institute literature explicitly states that Rolfing creates structural balance and includes movement education for functional integration, acknowledging Feldenkrais’s influence. Feldenkrais practitioners, too, sometimes refer students to Rolfers if they feel hands-on fascial work would help resolve an issue that movement alone is not addressing. - Addressing Habits on Different Levels: Alexander Technique is particularly good for the moment-to-moment awareness of habits in daily life (for instance, how you sit at your desk or the way you raise your shoulders when stressed). Feldenkrais tends to work through set-piece lessons that change habits at a broader neuromuscular level (for example, after a series of ATM lessons you might find you naturally sit differently, even if you weren’t explicitly thinking about it). Alexander can thus help maintain and refine the improvements gained by Feldenkrais or Rolfing by teaching conscious prevention of returning to old habits. Many Alexander teachers who have also done Feldenkrais note that Feldenkrais offers a wealth of novel movement experiences that can enrich an Alexander practitioner’s body awareness, while Alexander offers a clear framework for applying awareness in everyday activities and maintaining a poised state during any action

feldenkraisnow.org

feldenkraisnow.org

. For example, someone might use Alexander’s inhibition and direction while practicing a musical instrument, but also do Feldenkrais lessons to increase their overall flexibility and coordination, leading to greater ease when they play. Rolfing doesn’t explicitly train habit change in daily tasks the way Alexander does, so learning Alexander Technique after Rolfing can teach the person how to consciously sit, stand, and move in accordance with their new alignment. This ensures the changes “stick.” - Mind, Body, and Somatic Learning: All three methods engage the person in learning about themselves, which can be synergistic. Feldenkrais and Alexander are quite alike in instilling a mindset of curiosity and non-judgmental exploration. Someone who has taken Alexander lessons will find the Feldenkrais attitude familiar – both encourage being present to one’s body and avoiding self-criticism while learning new ways of moving. Thus, practitioners often cross-refer or even dual-certify. A few teachers are certified in both Feldenkrais and Alexander, using whichever approach best fits the student’s needs. In some cases, they might use Feldenkrais ATM exercises to loosen someone up and then Alexander hands-on to help them apply it to a specific skill. Rolfing and the others complement by covering the territory of direct tissue work, which Feldenkrais and Alexander do not do. For instance, if an Alexander teacher finds a student is extremely tight in a certain area despite their guidance, they might suggest a few Rolfing sessions to physically address that chronic tension. After Rolfing, the student often can progress faster in Alexander because the “roadblock” of tight fascia is reduced. There’s also a historical note: many individuals who pioneered somatic education in the 1970s (at places like Esalen) explored multiple modalities – it was not uncommon for someone to get “Rolfed” and then do Feldenkrais or Alexander lessons as part of an intensive personal growth process

feldnet.com

rolfing.org

. They found that the methods reinforced each other, leading to profound changes. While Rolf, Feldenkrais, and Alexander each emphasized their own approach, they acknowledged the value of the others. Ida Rolf’s admitting Feldenkrais influenced her and Feldenkrais’s praise of Rolf’s structural skill show a recognition that the ultimate aim – an integrated, well-functioning human – can be approached from multiple directions. - User Preference and Integration: Some individuals resonate more with one approach than another. For example, a very kinesthetic person who loves movement might prefer Feldenkrais ATM classes and Rolfing’s deep touch, whereas someone who is verbal and reflective might click with Alexander’s verbal-coaching style and do Feldenkrais primarily through one-on-one FI sessions. There is no rule that one must choose only one method. In fact, doing all three at different times can offer a more comprehensive somatic education: Alexander Technique trains conscious awareness and prevention of tension in everyday life, Feldenkrais provides creativity in movement learning and improvement of overall functional capacity, and Rolfing ensures the body’s physical tissues and alignment can support the new habits. Some practitioners schedule their learning in phases (e.g., first complete a Rolfing 10-series, then take weekly Alexander lessons to integrate, interspersed with occasional Feldenkrais workshops for extra movement variety). Because none of these methods conflict in principle – they all emphasize not forcing and improving awareness – a person can integrate elements from all of them. For instance, one might lie in Alexander’s constructive rest position (semi-supine) and incorporate a gentle Feldenkrais movement of the pelvis or shoulders while maintaining Alexander awareness of the neck. Or a Rolfer might teach a client an Alexander-style cue like “soften your neck” to help them receive the Rolfing touch without bracing. These hybrid uses show how fluid the boundaries can be when the practitioner understands the underlying principles.

In summary, the methods complement each other by filling in each other’s gaps: Rolfing adds a hands-on structural change component that Feldenkrais and Alexander lack; Feldenkrais adds a rich library of movements and a framework for neuromuscular re-patterning; Alexander adds a moment-to-moment mindful usage practice. All three together contribute to what pioneer somatic educator Thomas Hanna called “somatics” – education of the soma (the living, aware body) – and each enhances the overall goal of greater freedom and efficiency in one’s body and life. Ultimately, they contribute to a broader field of body-mind integration practices, and learning about all three gives a more complete picture of somatic education.

|

Notable Similarities |

– All emphasize awareness and education over symptom treatment. – Non-forceful approaches: encourage gentle change (even Rolfing, while deep, tries not to brute-force change – “no hammer and tongs” as Rolf said – Aim to integrate the whole person (body and mind) and often yield psychological benefits in tandem with physical improvements. – Each sees habitual patterns as the source of dysfunction and seeks to alter those patterns (Feldenkrais through novel movement, Alexander through conscious inhibition, Rolfing through tissue release). – All consider posture and movement as dynamic, not static – even Rolfing, though it works structurally, is about how the person will move and live in gravity afterward, not a posed “ideal” posture. – Practitioners of each often incorporate elements of the others (e.g. movement awareness in Rolfing, or discussion of skeletal alignment in Feldenkrais/Alexander). |

|

Notable Differences |

– Modalities: Feldenkrais = movement lessons and light touch; Alexander = light touch with movement coaching; Rolfing = deep tissue manipulation. – Active vs Passive: Feldenkrais ATM is active movement by student; Alexander is active mental participation with some assisted movement; Rolfing is mostly practitioner-driven changes with client passive (plus some active client participation). – Session format: Feldenkrais can be taught in large groups (ATM) or one-on-one (FI); Alexander traditionally one-on-one (with some group work for general instruction); Rolfing one-on-one only. – Immediate feel: Feldenkrais and Alexander are usually gentle and relaxing during the session; Rolfing can be physically intense during the session (though many find it a “good” release feeling). – Use of exercises: Feldenkrais has thousands of scripted lesson sequences; Alexander has no set exercises (focuses on applying technique in any activity); Rolfing has a standard 10-session recipe and may include prescribed movement homework. – Length of training: Alexander teacher training (~1600 hours/3 years) vs Feldenkrais practitioner training (~800+ hours/4 years); Rolfing training is shorter (~600 hours plus anatomy) but many practitioners have prior bodywork training. (This reflects the different skill focus: Alexander’s subtle hands-on vs Feldenkrais’s movement design vs Rolfing’s anatomical hands-on skills). |

Conclusion

Moshe Feldenkrais, F. M. Alexander, and Ida Rolf each forged a path toward greater human potential through the body, and their legacies have profoundly shaped the field of somatic education. Historically, their lives and work intertwined in interesting ways – from Alexander teaching the young Feldenkrais, to Feldenkrais inspiring Rolf, to Rolf and Feldenkrais collaborating as friends. Analytically, their methodologies can be seen as three complementary approaches to the same problem: how to help people move and live with more freedom, balance, and awareness. Feldenkrais offers a route through exploratory movement and neurological learning, Alexander offers a route through mindful inhibition of habits and refined guidance of the body, and Rolfing offers a hands-on route by altering the physical matrix that our habits and movements play out in.

Each approach has unique strengths and is best suited for certain individuals or issues, yet none of them is mutually exclusive. In practice, many people find value in more than one – for example, using Alexander’s thought cues while doing a Feldenkrais lesson, or maintaining Rolf’s structural achievements via a Feldenkrais practice. All three contribute to a larger understanding that our bodies and minds can learn at any age, that posture and movement are not fixed traits but dynamic skills we can cultivate.

By comparing Feldenkrais, Alexander, and Rolfing, we see a rich tapestry of somatic wisdom. Their differences teach us why posture involves not just bones and muscles but also habits, perception, and even emotion. Their similarities remind us that an integrated approach – considering structure, function, and awareness together – provides the most complete path to growth. These pioneers’ insights continue to be developed and integrated by new generations of somatic educators. Ultimately, whether one lies on a mat doing small movements, stands with a book on one’s head practicing inhibition, or works through a 10-series of deep bodywork, the goal is the same: a more embodied, efficient, and vibrant self. The legacy of Feldenkrais, Alexander, and Rolf is that they have given us multiple doorways into that experience.

Sources and References

- FeldenkraisMethod.com – Ida Rolf and Moshe Feldenkrais. (Anat Baniel tribute site). Contains Ida Rolf’s quote about not forcing change and her biography. feldenkraismethod.com

- FeldenkraisMethod.com – Ida Rolf & Moshe Feldenkrais – Dr. Feldenkrais Influenced Rolf’s Work. Describes Rolf naming Feldenkrais (specifically Body and Mature Behavior’s chapter on gravity) as an influence, and mentions their friendship and correspondence (birthday letter, Feldenkrais on Rolf’s death) feldenkraismethod.com

- Barnard Archives – Wellness Pioneer Ida P. Rolf, Class of 1916. Provides historical context on Ida Rolf, including her exploration of the Alexander Technique and other modalities in the 1940s. archives.barnard.edu

- Esalen.org – Back in the Day with Don Hanlon Johnson. An interview/article with Don Hanlon Johnson recounting the atmosphere at Esalen and anecdotes of interactions between somatic pioneers. Notably mentions an argument about the third cervical vertebra involving Rolf, Feldenkrais, and Alexander (illustrating their differing perspectives). esalen.org

- Feldenkrais Guild (feldnet.com) – Interview with Paul Rubin by Ira Feinstein (2017). A first-person account of meeting Moshe Feldenkrais at Esalen in 1973, where Feldenkrais and Rolf came to dinner and talked. Confirms Feldenkrais’s interest in Gestalt and that Rolf and Feldenkrais interacted socially. feldnet.com

- European Rolfing Association – Why not Osteopathy, Feldenkrais or Physiotherapy? (article). Written by a Rolfer, it compares Rolfing to Feldenkrais and others. Confirms that “Ida Rolf and Moshe Feldenkrais knew and valued each other” and that they discussed Structural vs Functional Integration. rolfing.org

. Also shares Feldenkrais’s 1976 letter quote about structure and function. rolfing.org

and notes the similarity and complementary nature of Rolfing and Feldenkrais (movement vs structure focus, inclusion of gravity concept). rolfing.org - CatherineMcCrum.com – About Moshe Feldenkrais. A biography snippet noting that Moshe Feldenkrais studied with F. M. Alexander and later developed Alexander’s ideas further, though they eventually quarreled. catherinemccrum.com

. Highlights the direct Alexander Technique influence on Feldenkrais. - Wikipedia – F. Matthias Alexander. Verifies historically that “Moshé Feldenkrais… had lessons with Alexander.”

en.wikipedia.org, confirming the direct connection between Alexander and Feldenkrais. - MarkJosefsberg.com – The Alexander Technique vs. Feldenkrais. Blog post by an Alexander teacher comparing the two methods. Provides background on how Feldenkrais drew from Alexander’s work and outlines differences in lesson formats and training hours

markjosefsberg.com

- FeldenkraisNow.org – The Pursuit of Poise. Article by a dual-certified Alexander and Feldenkrais practitioner discussing how he uses each method and the philosophical similarities/differences. feldenkraisnow.org

. Offers insight into how the two can complement each other in practice. - HudsonValleyOne.com – Somatic bodywork (Jennifer Brizzi, 2016). An overview article mentioning that Rolfing, Feldenkrais, and Alexander all improve alignment but via different approaches. Describes Rolfing’s basics (history, 10 sessions, involvement of exercises like arcing and pelvic tilts) hudsonvalleyone.com and situates all three as movement-based therapies for posture and pain.

- Rolf.org (Ida Rolf Institute) – Rolf Movement Integration. (Background info – not directly quoted above, but relevant). Emphasizes that Rolfing now includes movement education to reinforce structural changes, reflecting integration with concepts akin to Feldenkrais’s approach.

- Personal Experience and Training Literature. (General knowledge drawn from training materials, books, and practitioner notes by all three methods – e.g., Moshe Feldenkrais’s books Awareness Through Movement and Body and Mature Behavior, F. M. Alexander’s books The Use of the Self and others, and Ida Rolf’s Rolfing: Reestablishing the Natural Alignment and Structural Integration of the Human Body, as well as contemporary practitioner writings.) These informed the descriptions of lesson examples and typical outcomes.

Turn knowledge into body wisdom

Ready to move beyond theory? Experience how gentle movement awakens your body's innate intelligence. Join our journey where cutting-edge research meets embodied discovery, and transformation unfolds naturally.

Experience It Now